Leave the Gun; Take the Cannoli

New Orleans, March 14 1891: Eleven Italian immigrants are shot, hanged, and mutilated in front of a cheering crowd of thousands

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress (photo by Ken Light)

You probably know that Columbus Day falls on the second Monday in October; you may even know its original date (before Congress enacted the “Monday holidays”).

But you may not know that Columbus Day began as an apology to the Italian American community during a time of extreme prejudice against them, on the heels of what the Library of Congress calls “the largest single mass lynching in US history.”

This little-known tragedy evokes important questions about our Justice system, the bias of the Press, complicity of Politicians, and role of a Police Force. It also says a great deal about Ethnic Stereotypes, National Bigotry, and Attitudes toward Immigration – plenty of material for upper-level homeschool students.

The event that led to the establishment of a National holiday starts with the murder of a popular and respected Police Chief, David Hennessy, who, to his eternal shame, used his last breaths to utter a slur against Italians.

The Press, to its eternal shame, preemptorily condemned an entire community, harping on the idea that Hennessy’s murderers were part of a secret group called The Mafia.

City Mayor Joe Shakespeare disgraced his literary name by pinning the murder on “Sicilian Gangsters,” and ordering the police to “arrest every Italian you come across.”

Under pressure, the Police Force, to its eternal shame, responded with “mass arrests, forced searches, and beatings,” rounding up at least 100 Italian residents, most of whom were poor, working class, and connected to the murder by the flimsiest circumstances. One man was arrested because of his raincoat and another because his suit didn’t fit right. One of the accused was only 14.

Nineteen men, all of them Italian, were eventually put forward as suspects. The first nine experienced a trial characterized by unreliable witnesses, contradictory evidence, charges of jury tampering, a jailhouse assault, and other improprieties. In the end — after not a single one of them was found guilty – they were irrationally sent back to the prison.

The City was outraged by the verdicts.

The Daily States rang out, “Rise people of New Orleans” and the Times Democrat invited “All good citizens” to gather “to remedy the failure of justice.”

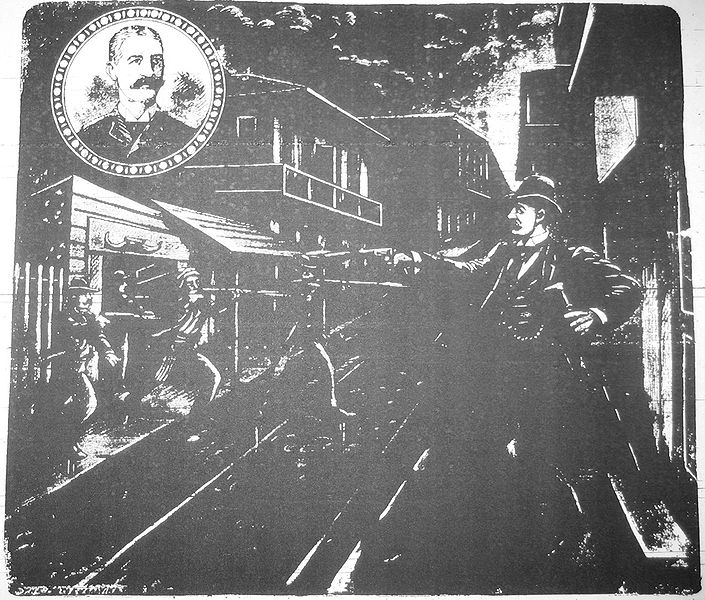

An angry mob gathered. They broke into the jail with a battering ram, with no intervention from the Governor/Mayor and little resistance from the Police. They shot some of the prisoners, beat others with clubs, and dragged a few out of their cells to hang. History.com describes the bodies as “riddled with bullets and torn apart by the crowd.“ Some of the more brutish participants mutilated the corpses and “plundered” them for “souvenirs.”

All told, 11 Italian men were killed that night – among them, five who had not yet appeared in Court and two who had nothing to do with the Hennessy Trial.

E. Benjamin Andrews (Scribner). Citizens use a beam to break

down the doors of the New Orleans jail.

Source: WikiMedia Commons

The Press approved: The New York Times referred to the dead men as “sneaking and cowardly Sicilians…” declaring that “Lynch law was the only course open to the people of New Orleans.” Despite the verdicts, the Washington Post titled its story, “Vengeance Wreaked on the Cruel Slayers of Chief Hennessy.”

Mayor Shakespeare said the men “deserved killing” and had been “punished by… law-abiding citizens.”

Sorry to say, this incident is part of a longer story. Catalysed by an influx of Italian immigrants (“The Great Arrival”) in the late 1800s, anti-Italianism encompassed negative stereotypes as well as violence and outright discrimination.

Journalists characterized Italians as criminals, insulted their appearance (“swarthy” was a popular description), and advanced the “theory” that “Mediterranean types” were inherently inferior to people of northern European heritage.

Lynchings occurred all over the country – New York to Missisippi – well into the 1900s. Among these were five men (the only Italians in the town) who were “taken from jail and hanged” in Tallulah LA, 1899. During WWII, Italians were another group harassed by their neighbors and rounded up by the Government. More recently, an NYC organization refused to erect a statue to Italian-American Frances Cabrini, according to a press release from the IAOVC.

Back in 1891, word of the New Orleans hangings spread through the country and round the world. The Italian consul in New Orleans (who had tried, in vain, to convince the LA Governor and Mayor Shakespeare to “do something”) resigned. His home country demanded prosecutions and compensation and cut off diplomatic relations with the US. Italian-Americans throughout the States (Pittsburgh, Chicago, Kansas City, NYC, Philadelphia) met to protest the violence.

Hennessy’s murder has never been solved. No action was ever taken against any one involved in the mob murder at the prison, either, though a Grand Jury was called. Prominent citizens who had joined (or incited) the murderous crowd went on, unimpeded by conscience or public outrage, to hold higher offices. And no reporter, columnist, politician, or LEO was ever called out, let alone disciplined, for his/her part in the tragedy.

But a payment was made to the families of the victims.

The City of New Orleans apologized.

And Columbus Day was proclaimed by Republican President Benjamin Harrison the very next year (1892).

HomeSchool Go 2 Postscript

What Can You Do with this Story?

Most of what’s known about this event comes from a book by Richard Gambino, Vendetta: The True Story of the Worst Lynching in America (1977). An HBO movie (also called Vendetta) was made in 1999; the title was used for several other movies, so be sure to read the summary.

Probably the best online descriptions are found here and here ; there’s also a contemporary piece (published 1891) here and a podcast here. As for the Trial, this article contains background and cast of characters information.

Image Source: WikiMedia Commons

Investigate President Benjamin Harrison who held office for one term (1889-1893) during an interesting period of American history. He may not make your Top Ten list, but in this event he deserves credit not only because he understood that the New Orleans lynching was wrong, but because he wanted to try to make things right, to publicly acknowledge that Italian-Americans are, in fact, Americans. He did so by issuing a Presidential Proclamation honoring a prominent Italian: Christopher Columbus, who (in 1892, the time of these events) had reached land exactly 400 years previously.

President Harrison intended the Columbus Day proclamation to be a one-time event. But the idea was so popular, and the Italian-American community so proud to have such recognition, that the holiday caught on and was ultimately made National by FDR. Find out more about the history of Columbus Day (some sources even trace the first celebration to the late 1700s)

Look into The Great Arrival (or Italian immigration in general). What prompted so many Italians to leave their homeland? Where did they settle? What did they do once there?

Italian American advocacy groups offer educational perspectives on current events as well as topics of interest such as the depiction of Italians in popular media, immigration history, and the preservation of Italian culture. Some are the Italian American One Voice Coalition; Italian Sons and Daughters of America; and the Conference of Presidents (of Major Italian-American Organizations).

In the days following Hennessy’s murder, the Press described Italians as criminals so frequently that “mafia” became a household word. How many times this week can you find an Italian character depicted as a Mafioso; can you find any positive depictions as well?

Teaching resources for Columbus Day are available here, here and here — as well as this unit based on Genevieve Foster’s The World of Columbus and Sons and an EdSitement lesson plan based on works of art.